Archaeologists continue searching for Battle of Red Buttes in west Casper

Courtesy Lillian Schrock and Casper Star Tribune, 6 June 2016 and 5 Sept 2016

What happened in June 1865 during a battle between 20 United States soldiers, led by 11th Kansas Volunteer Cavalry Commissary Sgt. Amos Custard, and 2-3000 Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapaho warriors at what has become known as the Battle of Red Buttes? Research since the 1920s has failed to reveal the exact location of the Battle of Red Buttes. A reevalutation of the battle including additional archaeological field and archive research has been ongoing since 2005 but have still failed to locate the battle or the mass grave. Twenty-five hectares were surveyed with Bartington magnetometers in 2012 and 2016. While a four hour battle may have an ephemeral archaeological footprint, it should still be visible because of the battle activities (i.e., burned wagon parts). Field studies in 2016 yielded the best evidence to date for the battle location, but definitive evidence continues to be elusive.

Wagon wheels. Horse bridles. Buttons from military uniforms. Human remains. These are among the items a group of archaeologists will be searching as they set out to find the site of an 1865 battlefield just outside Casper. The Wyoming Archaeological Society recently received $11,000 from the Wyoming Cultural Trust Fund to search for the Battle of Red Buttes. Though much has been written about the battle — which involved a large group of Lakota, Cheyenne and Arapaho and 25 Fort Caspar soldiers — the precise site of the conflict has never been found.

“It’s critical we locate this battlefield and burial,” said Carolyn Buff of the Wyoming Archaeological Society. For 10 days in late August and early September, four archaeologists and six volunteers will survey an area about five miles west of Casper. The group will use magnetometers to search for magnetic disturbances in the soil. They hope to locate signs of the battle, such as wagon parts and horse accessories. They also want to find the mass burials where the soldiers were interred.

“We need to find them for their living descendants,” Buff said. The archaeologists also worry housing and retail development in the area will encroach on the site, possibly ruining any chance of finding the lost soldiers.

This will be the third time the organization has sought to locate the battleground. The group first began searching for the site in 2008 after receiving a grant from the Natrona County Commissioners. They used metal detectors but nothing turned up. They tried again a few years later and began using the magnetometers, as well as cadaver dogs to search for human remains. Though they covered four times more ground than before, the scientists found nothing definitive.

If the burial sites are found, the scientists will notify the Natrona County coroner, who will determine if the remains are modern or historic. Then the soldiers’ living descendants will be made aware of the discovery. The archaeologists will study the remains and look for signs of trauma and disease before releasing them to the families for burial.

In September, Irish folk music wafted in the air as Dan Lynch painstakingly adjusted a machine mounted on a large yellow tripod balanced on a grassy hill. Casper Mountain rose behind Lynch. It was a hot Wednesday morning. The wind was calm. Lynch waved toward a man standing in the distance who was hoisting into the air a 2-meter red-and-white pole. Lynch pushed a button on his machine, called a total station, which sent a laser beam shooting toward the metal pole. The beam, invisible to the naked eye, reflected off a prism perched at the top of the pole and returned to the total station. Lynch and the other man, Danny Walker, were measuring the distance in order to arrange a 30-meter square grid over the project area.

Walker is the former assistant state archaeologist for Wyoming. Lynch is an anthropology professor at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. The two, with a group of other archaeologists, are searching for the site of the 1865 Battle of Red Buttes. This was their third attempt. The battlefield is the last major Indian war battle in Wyoming that has never been found, Walker said. “There’s 21 U.S. soldiers buried out here somewhere in an unmarked grave,” he said. “They could sell this land off for more housing, and they just built the new West Belt Loop. It could be destroyed by Casper getting bigger.”

Though much has been written about the battle — which involved 25 Fort Caspar soldiers and a large group of Lakota, Cheyenne and Arapaho — the precise site of the conflict has never been found. The group first began searching for the site in west Casper in 2008 after receiving a grant from the Natrona County Commission after being alerted to the possible destruction of the site from interested Casper historians and residents. They used metal detectors, but nothing turned up. They tried again a few years later and began using magnetometers, as well as cadaver dogs, to search for human remains. Though they covered four times more ground than before, the scientists found nothing definitive.

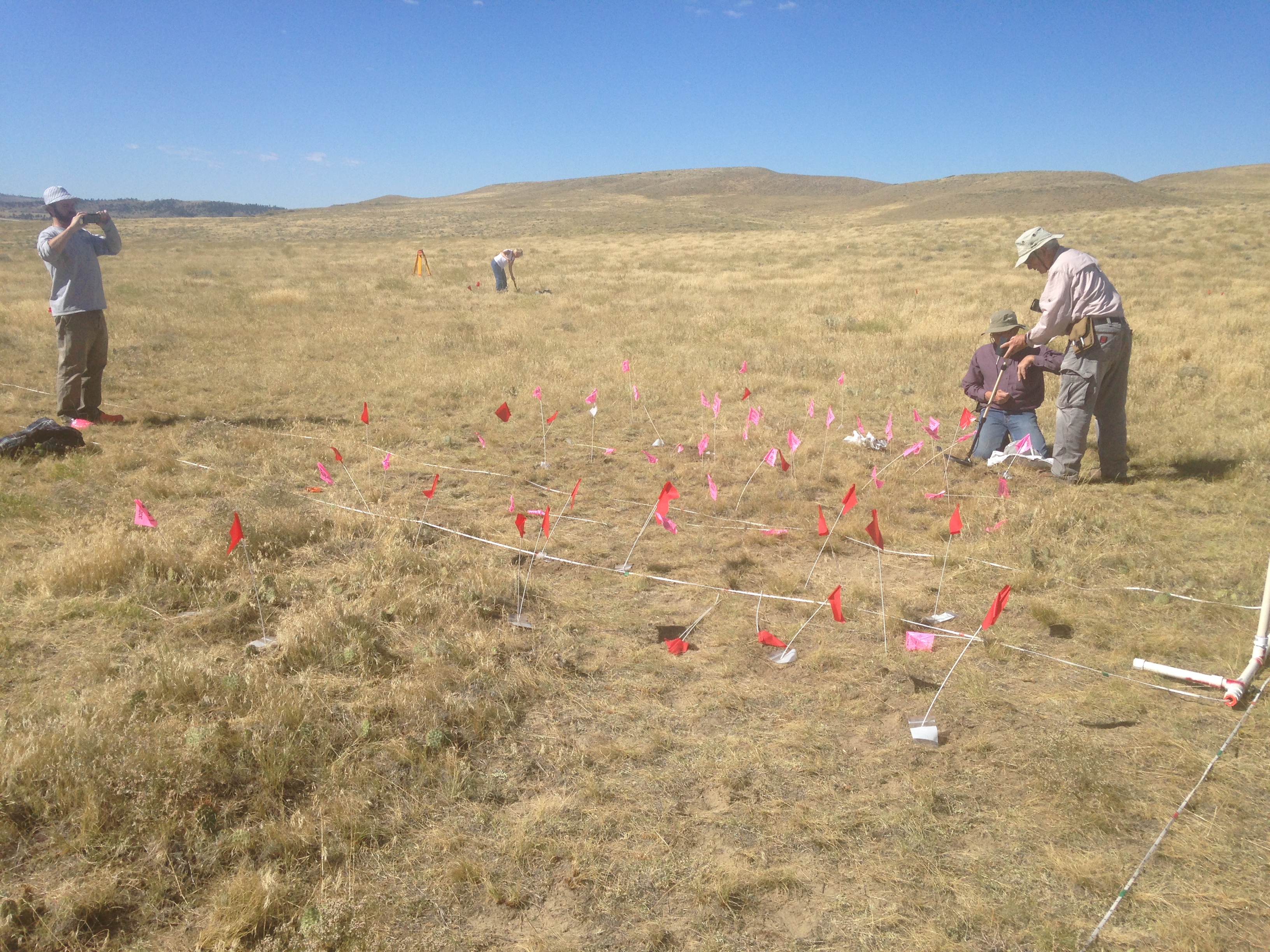

For this 10-day project, they were laying out a metric grid with rope. Then they will slowly and methodically push magnetometers through the grid. The archaeologists will upload their findings to a computer program and study any magnetic disturbances in the soil. Back on the grassy hill, the laser beam returned to Lynch’s machine. He spoke into a blue walkie-talkie. “Eighty-five centimeters backwards,” he said. Lynch could see Walker move the metal pole.

Stake in,” Lynch said over the walkie-talkie. Wayne Reynolds, Natrona County’s deputy coroner, was helping Walker. He pulled a stake out of a bucket and used a mallet to drive it into the ground before tying on a piece of red tape that showed the stake’s position on the grid. Each stake was placed a specific distance from a metal pole that served as a reference point called a datum. When the archaeologists push the magnetometers over the surface, a separate data file is saved for each square on the grid. That way when they analyze their data on a computer, they will know exactly where on the survey site they are looking.

On a nearby hill, Rory Becker strode slowly back and forth between white ropes laid on the ground. His hands were placed on a white pole in front of him, as though he was riding a bicycle. Two white metal rods were attached vertically on each side of the pole. A small electronic box between his hands beeped rhythmically as he walked. The machine was one of two magnetometers the group is using to survey 120 of the 30-meter squares. Becker, who wore a white t-shirt and a safari hat, had replaced the buttons in his khaki pants with plastic ones so as not to interfere with the machine’s magnetic work. He wore a small backpack with weights inside to counterbalance the weight of the magnetometer. I love the history part of it,” he said. “But it’s also important to me that we find these folks before development runs them over. We want to have it protected rather than have it accidentally run over by a bulldozer.”

Becker, an anthropology professor at Eastern Oregon University, was looking for wagon parts, horse bridles, buttons from military uniforms and perhaps a burial trench. The magnetometer doesn’t provide a real-time view. Instead, he’ll have to wait to upload the data to his computer. A program called TerraSurveyor will convert the data into an image Becker can analyze. It will take months for him and the other scientists to produce a final report on the project.

Connie Jacobson, the Natrona County coroner, adjusted the ropes marking the grid as Becker moved through the grass with the magnetometer. Should the magnetometers spot remains, Jacobson will be tasked with determining if the bones are human and if they’re modern or historic. Then the soldiers’ living descendants would be told of the discovery. The archaeologists would study the remains and look for signs of trauma and disease before releasing them to the families for burial. I feel like I need to help in the front end instead of just being called in if human remains are found,” Jacobson said.