Hell Gap Site (48GO305)

The Hell Gap site is located in southeast Wyoming, on the eastern edge of the Hartville Uplift. The uplift is a geological feature that rises slightly above the surrounding terrain, especially the plains to the east. Because of its multiple exposed geologic formations, Hartville Uplift provided prehistoric inhabitants with a myriad of different stone sources for making of stone tools. Wyoming’s hunter-gatherers used the rich stone sources in this area from the earliest prehistoric times.

Hartville uplift also provides a diverse ecological setting for hunter-gatherers. To the east are the open grass plains with prairie potatoes, buffalo, pronghorn, and many other plant foods, animals, and medicines. To the west the uplift sports a ponderosa pine savannah with juniper, wild onion, sago lily, deer, and other important plant and animal foods, and medicines. The ecotone – boundary between these two major ecological zones – is particularly advantageous as an access point to both resource sets. In addition, Hell Gap valley provided water for most of the year during the Late Pleistocene and early Holocene times.

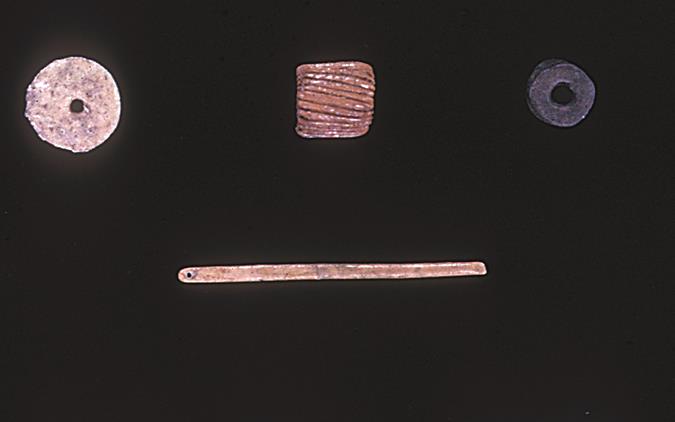

Hell Gap is an early, stratified North American archaeological site that provides data for the lifeways of the Frist Americans (Paleoindians), from about 13,000 to 8500 years ago. On numerous occasions Paleoindians camped in the Hell Gap Valley for short periods (estimated from a few days to perhaps as long as a month), and left the remains of camping along the banks of the creek. Structures, stone tools (Figure 1), debris from production of stone tools, ornaments (Figure 2), bone tools such as awls or needles (Figure 2), food refuse are some of the items left behind and buried by the arroyo flood waters or sheetwash from the nearby slopes. Archaeologists have been investigating these remains for nearly 60 years.

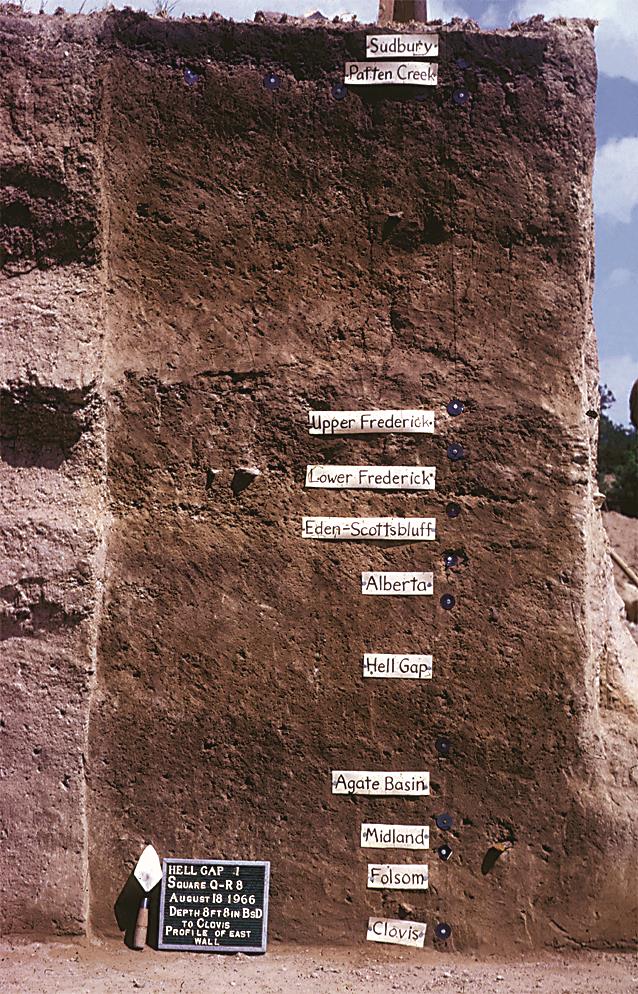

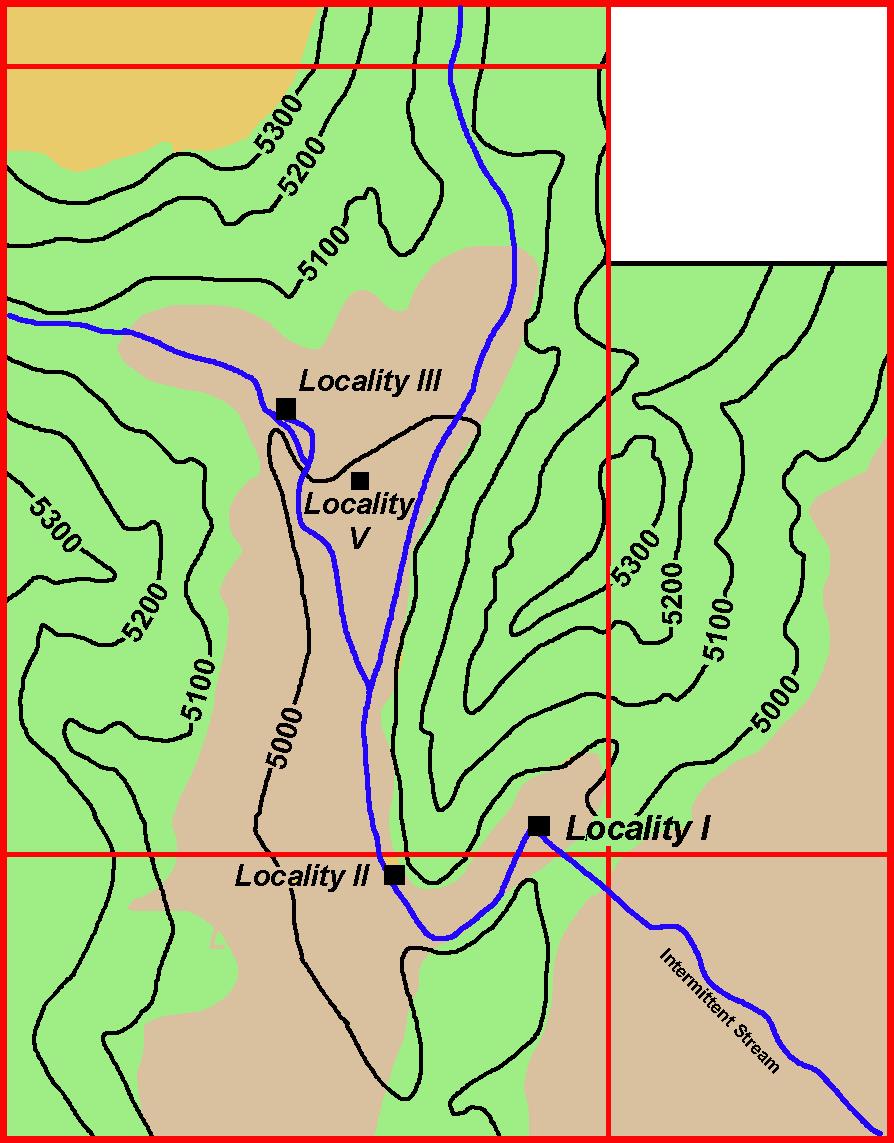

Beginning in 1959, excavations documented the basics of the archaeological record of the Hell Gap Valley, four Paleoindian localities (Figure 3), each with a sequence of cultural components (Figure 4). This established the site as a key Paleoindian locality, not only in Wyoming, but for North America. The 1960s (1962-1966) investigations recovered critical data and are still the basis for what we know about the site today.

Renewed investigations of the early 1990s were designed to provide better context for the large collection of artifacts recovered during the 1960s. The main goal of the 1990s studies was to write a comprehensive report of the Hel Gap site (not done before). The goal was partially accomplished through one publication (Hell Gap: A Stratified Paleoindian Campsite at the Edge of the Rockies, edited by M.L. Larson, M. Kornfeld, and G.C. Frison, 2009, University of Utah Press), but the work continues. A significant goal since 2001 has been the elucidation of the Hell Gap cultural stratigraphy brought into question as a result of 40 years of Paleoindian research, radiocarbon dating revolution, and developments of archaeological field methods. The data for unravelling (verifying or rejecting) the original (1960s) Paleoindian cultural sequence of the Hell Gap site can only be accomplished with detailed field techniques (Figure 5) and sophisticate spatial analyses. We have nearly completed the former, but have hardly begun the latter.

Hell Gap site was acquired by the Wyoming Archaeological foundation, a non-profit entity (dedicated to learning from and preserving archaeological resources), through outright purchase and gifts in 1988. In addition to the site’s research potential, the WAS property provides a fantastic venue for public education.

Ecology, climate change, human adaptation to changing environments, cultural evolution, are some of the topics that can be (and are) part of the public programs at Hell Gap. The annual fieldwork and field schools train and provide experience to many students and avaocational archaeologists in the latest archaeological field techniques. Annual visitation to the site includes underserved local communities (Figure 6), visitors from throughout North American and oversees, as well as international scholars (Figure 7). Current research phase at the site will likely be completed within five years, however, we expect to raise more questions, requiring future studies.

Figure 1. Projectile point sequence recovered from Locality I of the Hell Gap site. From oldest (left) to youngest (right): Goshen, Folsom, Midland, Agate Basin, Hell Gap, Alberta, Scottsbluff, Frederick, and Lusk.

Figure 2. Bone and stone beads (top) and bone needle (bottom) from the Hell Gap site.

Figure 3. Hell Gap Locality I profile showing cultural complexes represented and their location in the stratigraphic profile.

Figure 4. Hell Gap Valley showing location of the four major Paleoindian localities.

Figure 5. Excavation and computerized recording system used at the Hell Gap site.

Figure 6. Maryann Koonz with third grade class from Wheatland, excavating at the Hell Gap site, Locality I.

Figure 7. Visitors to the Hell Gap site in 2009. Maris Krstic from Croatia explains stratigraphy, excavation procedures, and findings. Renata Nizak from Croatia looks on from far left.

Figure 8. Professional and international visitors to the Hell Gap site in 1966 (top) and 2016 (bottom). The 1966 Denver meeting of the International Quaternary Association and the 2016 Suyanggae and Her Neighbors: Suyanggae and Hell Gap symposium in Laramie.